|

LITTLE SWITZERLAND BREWERY RISE & FALL Thoughts on What Happened - by J.S.  During the early 20th Century, more than 1,400 U.S. breweries were forced to shut down due Prohibition. The Fesenmeier Brewing Company of Huntington, West Virginia was among 756 to reopen when the "Noble Experiment" ended in 1933. But rough waters lay ahead. A significant number of firms closed immediately because their brewing equipment had been sitting idle too long and could no longer produce drinkable beer. Fesenmeier was an exception. They refurbished their old brewery buildings, installed $300,000 worth of modern equipment, purchased 30,000 wooden beer crates and 17 train-carloads of bottles – nearly a million bottles - in preparation for the end of Prohibition. In the years that followed, more beer was being produced by fewer companies due to closings, acquisitions and mergers, a pattern that accelerated after the arrival of television in 1949. About 165 American breweries were still operating in 1968 when Fesenmeier changed hands to become "Little Switzerland Brewing Company." Within 5 years that number would drop below 75. Only about 40 remained in the early 1980s, when the craft-beer revolution began to change things for the better. By 2013, the number had long surpassed pre-Prohibition levels with no signs of stopping, reaching 2,483. As of 2024 there are more than 9,000 breweries in the United States, a number unfathomable in days of yore. During the early 20th Century, more than 1,400 U.S. breweries were forced to shut down due Prohibition. The Fesenmeier Brewing Company of Huntington, West Virginia was among 756 to reopen when the "Noble Experiment" ended in 1933. But rough waters lay ahead. A significant number of firms closed immediately because their brewing equipment had been sitting idle too long and could no longer produce drinkable beer. Fesenmeier was an exception. They refurbished their old brewery buildings, installed $300,000 worth of modern equipment, purchased 30,000 wooden beer crates and 17 train-carloads of bottles – nearly a million bottles - in preparation for the end of Prohibition. In the years that followed, more beer was being produced by fewer companies due to closings, acquisitions and mergers, a pattern that accelerated after the arrival of television in 1949. About 165 American breweries were still operating in 1968 when Fesenmeier changed hands to become "Little Switzerland Brewing Company." Within 5 years that number would drop below 75. Only about 40 remained in the early 1980s, when the craft-beer revolution began to change things for the better. By 2013, the number had long surpassed pre-Prohibition levels with no signs of stopping, reaching 2,483. As of 2024 there are more than 9,000 breweries in the United States, a number unfathomable in days of yore. A mere handful American brewing companies currently in existence have any ties to Prohibition. They are now reaping the benefits of the craft-beer movement because they took an active role in nurturing it, first by continuing to make honest beers and limiting their supply and distribution area, and later by experimenting with world-class styles. With its logistical and competitive advantages, the Huntington brewery should have been part of it. Why wasn't it? What if it had been? A New Beginning

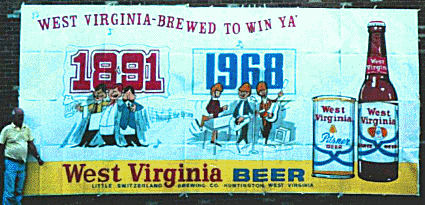

It has been reported that production of Fesenmeier Centennial continued for a period of time, as the brewery's business-plan proposed. But so far, no one knows how much nor for how long. One plausible theory holds that they simply bottled and/or distributed the leftover Fesenmeier Centennial product until that summer, when they introduced two new brands: Charge "The Bold American Premium Beer," and the budget-priced Innkeeper Beer. A 3.2 % Nightmare, One of The Camel's Least Favorite Straws The brewery's new owners were quite fortunate to have Alan L. Hann as brewmaster & production manager, and Jack Berno as executive vice-president and general manager. Each of these men were internationally recognized in the brewing industry and spoke with justifiable confidence about their products. Little Switzerland offered shares of stock for sale only to residents of West Virginia, and hoped to make the brewery a major tourist attraction. However, one thing they could not provide to consumers in the "Switzerland of America" was beer above 3.2% alcohol. In order to taste the higher-strength versions of their products, one had to go to Ohio or Kentucky where several bordering cities and counties remained dry under local option laws. The problem of having to produce two separate batches of each beer made it difficult for the brewery to stay profitable. Ownership proceeded to pour money into new labels, signs and all associated items; as well as modernizing the plant's production area, with additional improvements to the offices and hospitality room. The office buildings were adorned with a Swiss motif, which in hindsight did not look all that spectacular. The Name Change The decision to re-name the Fesenmeier brewery and drop the flagship brand has never been explained, though it may be that issues with licensing and / or trademarks were a factor. But whatever the case, new ownership would have been well-served to overcome any such obstacles. The Fesenmeier family had been inthe city of Huntington for almost 70 years, their brewery surviving floods, fire and a 19-year prohibition that began in 1914 - five years before the law took  effect nationwide. For 34 years the plant had been known by the family name. effect nationwide. For 34 years the plant had been known by the family name. In general, some amount of risk is to be expected when a successful company changes ownership, but overcoming a change in name - particularly one as recognizable as "Fesenmeier" can be tricky. The very sale of the brewery no doubt sent a shock-wave throughout its marketing and distribution system. Clever as it was, the change to Little Switzerland probably created some sort of disconnect among retailers and consumers alike. Continuing to do business as Fesenmeier would have eased the offending shock-wave. Perhaps it might have made more sense to return to its former name, The West Virginia Brewing Company, given the fact that the West Virginia brand was once again the flagship and that company stock shares could only be purchased by those living in the State. Still, without a new name, more time and attention could have been devoted to keeping the brewery afloat. Instead of being mired in start-up costs, loads of cash would have been saved by leaving the product labeling unchanged - everything from bottles and cans to brewery trucks, signs, cartons, letterhead, envelopes, etc. Additionally, with no Swiss motif to worry about, a much more cost-effective remodeling job could have taken place, concentrating only on the plant's critical needs, such as upgrading the offices and brewing equipment. Even though production of West Virginia Pilsner continued, new ownership opted to change the memorable slogan, "West Virginia - That'll win ya!" to - "West Virginia - Brewed to win ya!" The original slogan was a bold statement of excellence that projected confidence to both old and new consumers of West Virginia Beer & Ale. The re-vamped slogan appeared to be aimed at consumers who did not yet exist. It lacked  confidence, coming off more as a plea; thus, confusing the brand's otherwise solid link to the past. confidence, coming off more as a plea; thus, confusing the brand's otherwise solid link to the past. Conversely, their slogan for Charge was quite imaginative: "Take Charge, The Bold American Premium Beer" - with another, lesser-known permutation directed at baby-boom hipsters, "Young America is Taking Charge." This second slogan itself was a stroke of genius because at the time much of young America was seeking out lesser-known brands of beer made by obscure companies. Boomers traveling in the U.K and Europe had tasted so-called "real" beer; and Charge was a "real" European style beer. Craft Beer Jack Berno stated in an interview that Little Switzerland was making beer (we assume Charge Premium) in accordance with the Bavarian purity law, Rheinheitsgebot, adopted in the year 1516, which decreed that only malted barley grains, hops, yeast and water be used in the making of real beer. In other words - all malt - free of adjunct ingredients. All of the hops and part of the barley in Charge were imported, giving it bold flavor characteristics that were out of sync with the times. The use of use corn, rice and other adjuncts had been commonplace among pre-prohibition brewers, but it accelerated following World War II, as most Americans began to demand lighter beers. The Fesenmeier's used cornflakes in at least some of their products. While there is nothing inherently wrong with this kind of beer, the taste is noticeably different from beer made exclusively with the Rheinheitsgebot ingredients. It should be mentioned that some folks today believe craft beer cannot be made with adjuncts. They are wrong. Many products falling into this category are full of adjuncts including (but not limited to): oats, rye, honey, spices, chocolate, potatoes, coffee, fruit, and yes - even corn and rice. The terms "adjunct beer" and "craft beer" have been co-opted much in the same way the terms "free-range," and "organic food" have. "Craft brewing" best describes the approach for making beer. It does not necessarily describe the size of the brewery, nor the ingredients used, nor the vessel to package it in. That said, Alan Hann's goal was to brew at least one all-malt, chemical-free "import-style" beer in of all places, Huntington, West Virginia. An impressive feat in the days before the craft beer revolution. Had officials at Little Switzerland been more in tune to what Fritz Maytag was doing out in California, they could have taken their "approach" a step further and become one of the pioneer regional-craft/specialty brewers like Anchor. Maytag's purchase and rescue of San Francisco's failing Anchor Brewing Company in 1965 is generally referred to as the birth of the American craft beer revolution. People throughout the industry thought he was completely nuts because his brewery was the smallest in the country and he was set on making all-malt beers. At first his product wasn't very good but he forged ahead. And by 1970, Maytag and his associates had perfected the recipe for the beer that would forever change the course of brewing history, Anchor Steam. While brewers elsewhere in the U.S. (most notably the big nationals) raced to turn beer into a straw colored, watered down, mass produced commodity that was no more spectacular than  tins of tuna fish, Maytag was busy producing Anchor Steam in small batches, adding a bottling line in 1971 in order to keep up with demand. But regardless of the success Anchor Brewing Company was achieving, their market share was so small that it barely registered a blip on the radar. A tiny fragment of grain in a field of barley. American beer was in danger of losing its identity. tins of tuna fish, Maytag was busy producing Anchor Steam in small batches, adding a bottling line in 1971 in order to keep up with demand. But regardless of the success Anchor Brewing Company was achieving, their market share was so small that it barely registered a blip on the radar. A tiny fragment of grain in a field of barley. American beer was in danger of losing its identity.Following the end of World War II, many U.S. brewers began making lighter versions of their beers in an effort to appeal to female drinkers. This type of mass-market adjunct brewing accelerated in the years that followed and dominates the US beer market today. In this case Fesenmeier had been "light years" ahead of the curve, producing several products in response to public demand for lighter beer: West Virginia Pilsner - beginning in 1941, West Virginia Extra Pale Pilsner in the late 1940s, and West Virginia Light (in cans!) as early as 1955 and as late as 1964, making them one of the first to use the term "light" successfully. This movement influenced the "diet" beers of the late 1960s - the dawn of the low-calorie light beer craze. Thanks to the success of Lite Beer from Miller in the mid-1970s, every brewing company soon had its own version of light beer, putting the nation's taste into a coma by the 1980s. In spite of the craft beer revolution, most Americans still prefer to drink light beer. Consequently, the three biggest-selling brands in the U.S. today are: Bud Light, Lite Beer from Miller, and Coors Light. Showdown in the Ohio Valley Back when Little Switzerland opened in 1968, craft-breweries like Anchor were just a flicker of light on the horizon. Home brewing and brewpubs were still illegal in all states, casualties of Prohibition. Anheuser-Busch (A-B) opened their Columbus, Ohio brewery that same year, making the Ohio Valley market more accessible to them than ever before. At last, the stage was set for a showdown between the independent breweries operating in this territory and Anhueser-Busch. While other nationals like Schlitz, Carling, and Pabst had an impact, they were in serious trouble by this time and were literally scrambling for ways to compete with A-B. Little Switzerland was blessed with built-in logistical and competitive advantages that larger brewers couldn't match. It was the only brewery in West Virginia, and the only one within 150 miles of Huntington. To the west was Hudepohl, Burger, and Schoenling in Cincinnati; Falls City in Louisville; and Wiedemann in Newport, KY - who had just  been given a new lease on life in 1967 when they were purchased by G. Heileman. To the north was Anhueser-Busch and August Wagner in Columbus, Stroh in Detroit, and Pittsburgh Brewing in Pittsburgh (no kidding?). been given a new lease on life in 1967 when they were purchased by G. Heileman. To the north was Anhueser-Busch and August Wagner in Columbus, Stroh in Detroit, and Pittsburgh Brewing in Pittsburgh (no kidding?). For a long time, Stroh and Falls City appeared to have been investing more heavily in the Huntington market than anyone. As a result, their flagship brands were arguably the two most popular beers in the Greater Huntington area. Pittsburgh's Iron City brand was more prominent throughout the remainder of West Virginia, once considered Fesenmeier's "bread & butter" market area. Together with Anheuser-Busch, they would present the biggest challenge for the Huntington brewery. Few beer makers could afford to be aggressive in their penetration of West Virginia because it put a strain on their brewing capacities to make special batches of 3.2% alcohol beer. For this reason, some firms kept their products out of the Mountain State entirely. On the other hand, Anhueser-Busch was able to brew unlimited amounts of 3.2% beer in their huge, spanking-new Columbus brewery. A-B was on a seek & destroy mission, and utilized record amounts of advertising along with aggressive "soon-to-be-legendary" distribution and pricing tactics to eliminate their competition one by one. The latter included cutting its own profit margins and forcing other brewers to compete on price by dumping large quantities of beer into their market areas. Even at full-capacity, the Hunrtington brewery was the smallest concern of them all and had no business getting involved in the fight. It was David against a slew of Goliaths. After being sold again three years later, Little Switzerland had the dubious distinction of being the first in this group to shut down, and the only one whose brands would completely disappear forever, never to be picked up by another brewing company; that being perhaps the biggest slap in the face. They were to be followed by Burger in 1973, whose brands were acquired by Hudepohl. Next was the brewer responsible for purchasing and closing Little Switzerland in the first place - August Wagner, who sank in their own sea of debt in 1974, their brands acquired by Pittsburgh. Falls City shut its doors in 1978 after failing in their attempt gain national prominence with Billy Beer, their brands absorbed by G. Heileman - who closed down the Wiedemann plant in Newport in 1983. Production was transferred to Heileman's Evansville brewery. Eventually the Falls City brand was acquired via Evansville by Pittsburgh, who discontinued its production in 2006. In 2009, a Louisville entrepreneur acquired the trademark and re-launched Falls City as a premium craft beer. Hudepohl merged with Schoenling in 1986. Two years later, they entered into an agreement to brew small batches of hand-crafted beer for the Boston Beer Company, who purchased the Hudepohl-Schoenling brewery outright in 1997 - and then sold the brands off to an out-of-state company in 1999. In 2004, a Cincinnati firm began the process of bringing the Hudephol 14K, Schoenling, and Burger brands home to the Queen City,  culminating in their successful 2009 relaunch. However, production remains under contract brewing arrangements with other regional brewers. Boston Beer still operates the Cincinnati plant, which underwent a multi-million dollar renovation in 2005. It is known today as The Sam Adams Brewery. culminating in their successful 2009 relaunch. However, production remains under contract brewing arrangements with other regional brewers. Boston Beer still operates the Cincinnati plant, which underwent a multi-million dollar renovation in 2005. It is known today as The Sam Adams Brewery.Stroh Brewing of Detroit mounted a quest to go national beginning in 1981 with the purchase of F & M Schaefer. Later acquisitions included Joseph Schlitz in 1982, making Stroh the third largest brewer in the United States. Their plan worked for little while before sales began to drop. In an ill-advised move in 1996, they purchased the bankrupt G. Heileman Brewing Company. By 1999, Stroh was out of the brewing business for good, its brands going to Pabst and Miller. Following years of ownership changes and serious financial woes, Pittsburgh Brewing Company filed for bankruptcy protection under Chapter 11 in January 2006. The company continued to operate as events unfolded and by 2007 they had a new group of investors and a new name, Iron City Brewing Company. However, due to the cost estimates of refurbishing the original Lawrenceville plant, production was shifted in 2009 to City Brewing Company in Latrobe (formerly the Rolling Rock plant). The move was designed to save money and further bolster the survivability of the Iron City brand. In 2022 Pittsburgh Brewing Company opened a new facility in a former glass plant in Creighton, PA about 18 miles from downtown Pittsburgh. Supply and Demand For the majority of the smaller regional breweries there were few options for staying open. In the mid-1960s, virtually no company with pre-prohibition roots thought about carving out their own niche, limiting their distribution to local areas and letting demand for their product exceed the supply. Stevens Point Brewing did just that, following the supply and demand rule. It was a struggle but they marched to their own drummer and simply got on with the business of making good beer instead of stretching themselves and their ingredients too thin. The brewing of world-class beer in small batches simply did not enter the minds of brewery owners. Like Little Switzerland, the vast majority were still trying to compete head-to-head with the nationals, who themselves were busy fighting it out with each other and anyone else willing to step into the ring.  Pre-prohibition brewing companies still operating today: Pre-prohibition brewing companies still operating today:August Schell - New Ulm, Minnesota, hometown of one of our contributors, Steve Fesenmaier. FX Matt Brewing Company - Utica, NY The Lion Brewery - Wilkes-Barre, PA

Stevens Point Brewery - Stevens Point, Wisconsin

Straub Brewing Company - St. Marys, Pennsylvania D.G. Yuengling - Pottsville, Pennsylvania - America's oldest brewery Little Switzerland fit the basic profile of the surviving independents listed above rather nicely. For one thing, it was a small operation with a desire to make superior beers. For another, they were only a few years removed from the old styles of beer the Fesenmeier's once produced. Pale ales and seasonal beers were a common sight on the plant's bottling lines up until the 1950s, along with bock beer until 1966. But new ownership clearly had no intention of finding a niche, and spoke of building the Charge brand into a nationally recognized product. Fesenmeier's brewing capacity was 100,000 barrels but production peaked at only 60,000 barrels in 1949. In 1966, while other small brewers were wallowing in debt, the Fesenmeier Brewing Company was still a profitable and worthwhile venture, selling just under 30,000 barrels and netting about $38,000 after expenses (over $250,000 in today's economy). By contrast, in 1966 Budweiser became the first brand in history to sell 10 million barrels in a year. That's 30,000 barrels a day, the same amount Fesenmeier sold for all of 1966! In 1975, Anchor Brewing Company turned a profit for the first time in the Maytag era and never looked back. Maytag retired in 2010 and sold the brewery. In 2017 it was sold to Sapporo, which had the mistaken notion that they could turn this quirky ale brewery into a lager brewery. The plan failed miserably. Sales declined over the next several years, and workers became increasingly disenchanted with the direction Sapporo had taken Anchor. Sadly, in 2023 Sapporo shut down Anchor for good and liquidated its assets. But there was light on the horizon. In 2024 a new owner acquired the Anchor brands with intentions of keeping operations in San Francisco. Look for updates on this developing story. Priorities The Little Switzerland business-plan clearly states, "The company believes itself to be capable of the production and marketing of beer, ale and allied products at a profit, despite intense competition on the national level." In light of this, the first priority of the company should have been to quickly determine exactly "where" the customer base was located Had they chosen to stay under the radar and limit their marketing and distribution area while focusing on the production of a single flagship brand, Little Switzerland might still be here today. Instead, they attempted to introduce a new company and two new brands. Not only that, they proposed to expand production and distribution in a market that was already saturated by the big nationals and larger regionals like Stroh and Falls City. By early 1970, the owners were lobbying the West Virginia Legislature to grant the brewery a tax-credit to keep it open. They even went so far as to host an event at the Daniel Boone Hotel in Charleston, where lawmakers could sample the beverages produced at Little Switzerland. Despite their best efforts the tax-credit failed and the facility went bankrupt in October 1970. It was quickly sold to August Wagner of Columbus, Ohio, which planned to brew its products in Huntington, including the well-known Augustiner Beer. But something went wrong and they closed the brewery for good in 1971. It is unclear whether the plant sat idle or if August Wagner continued to produce Little Switzerland beers before they shut it down. Perhaps the 3.2% alcohol limit was one of the sticking points that kept the Columbus brewer from following through with their plans? Imagine if Little Switzerland had Survived  Imagine if Little Switzerland or Fesenmeier had somehow managed to survive another 15 years into the mid-1980s? West Virginia's 1981 repeal of the 3.2% limit, allowing for the sale of beers up to 6.0%, along with the micro and craft-brewing revolution surely would have helped breathe new life into the brewery. If you have a brewery near you, support it. If you're traveling, drink the local brew. Don't believe us? Take a look at the former Fesenmeier brewery being destroyed.. Yes, it's okay, you're allowed to vomit.

Photo clipping from the Herald-Dispatch. Additionally, Central City saw a major rebirth in the 1980s as the antique-capitol of the Tri-State, a tradition that continues to this day. It is without question that a brewery of any size with strong ties to the old neighborhood would have been the cornerstone of that rebirth. A beacon of pride and a major tourist attraction, celebrating an ancient craft and thus, fulfilling the dream of Little Switzerland's owners. At the end of the day, the big nationals were not alone in putting independent brewers like Fesenmeier and Little Switzerland out of business. Beer drinkers played a major role. Most were duped into believing the slick advertisements by the big guys - and so they made their choices, oblivious to the consequences until it was too late. Americans have a bad habit of voting against their own self-interest. They do it with politics as well as with their dollars. With one or two exceptions, all reports indicate the beer produced by this brewery from 1899 -1971 was equal or superior to the competition. In July of 2009,West Virginia passed "The Craft Beer Bill" into law, permitting the sale of beers as high as 12% alcohol. Those of us with a palate for craft beer can only imagine what sorts of offerings might be rolling off the production lines at Little Switzerland if it were here today. Photos of West Virginia billboard poster, Little Switzerland keg top, West Virginia pennant, and Charge bottle caps - courtesy of Phil Dobeck Photo of Fesenmeier tray by J.S. - tray from the collection of Phil Dobeck All other photos by J.S. Related Links: falstaffbrewing.com John Smallshaw's excellent Falstaff website Shakeout in the Brewing Industry - from Beer History.com |