The following article is one of the best written accounts of the Fesenmeier Brewing Company in existence. It originally appeared in the amazing Goldenseal Magazine, published and distributed by the State of West Virginia - Division of Culture and History. It is with kind permission from both the author, Steve Fesenmeier, and from Goldenseal Magazine, that we are able to present it to you in its entirety. This website would not be complete without it. To visit the Goldenseal website and/or subscribe, please click HERE.

(Goldenseal - Volume 7 Number 4, Winter 1981)

I grew up in a German-American family in Minnesota, drinking beer from my early years. Beer was and is - the national drink in Germany, and German immigrants brought the custom with them to America, eventually popularizing the beverage in their new country. At home we drank beer in moderation at mealtime, and socially on festive occasions. We drank it, but we had never brewed it, so far as I knew.

Then one day my Grandfather Hugo showed the family a can of “Fesenmeier Beer,” brought back from the East by one of the in-laws. No one took the can seriously, thinking the relative picked it up at some state fair which custom-printed cans of beer with the buyer’s name on them. The Fesenmaiers we knew had never been anything but farmers and mechanics, along with a few eccentrics like my Uncle gene, boxing promoter and manager. Years later I wrote to the Beer Institute in Washington, inquiring about such a brand, and heard nothing from them.

But a surprise awaited me when I moved to Charleston in 1978 to become head of Film Services for the West Virginia Library Commission. When I told my new friends that my last name was “Fes-en-maier,” many responded, “Did you say ‘Faz-en-mayer’? I used to drink a lot of that beer back before they closed down a few years ago.” It seemed that perhaps some distant relative, with a different pronunciation and slightly different spelling of the name, had beat me to West Virginia.

I knew the history of my own family fairly well. The Fesenmaiers were among the early German settlers of Minnesota, dating back to the 1840s. The story goes that three brothers came to the New World from Wurtenberg – one going to the Milwaukee area, one to Baltimore, and one to Wisconsin and then on to Minnesota.

The Minnesota Fesenmaiers eventually settled in New Ulm, a town founded as a utopian commune by idealistic and industrious Germans. The Fesenmaiers stayed around New Ulm, and built a good reputation among families of the area. Our Fesenmaiers were enthusiastic beer drinkers, but evidently none of them had ever become brewers.

The West Virginia Fesenmeiers were another matter, for they’ve been brewers and brew masters for generations. Rebecca Fesenmeier Kayes, now living in Huntington, once recalled that “my family has been connected to the brewing business since the early 1800’s; then my grandfather in Cumberland, Maryland, and later Huntington, and now my father and two uncles.” Mrs. Kayes wrote those words for a high school English project nearly 20 years ago, and her father and uncles are now dead, as is the family business in Huntington.

These Fesenmeiers established themselves in America in 1851. In that year Michael Fesenmeier brought his bride to a farm on the old National Road near Cumberland. He had learned to make beer while still a boy in Germany,  and shortly after the Civil War he started a small brewery on his Maryland farm. As demand grew, he expanded his operation. Refrigeration was the biggest problem, and that was solved by harvesting natural ice in the winter months and storing it in vaults dug into a hillside between the brewery and the farmhouse.

and shortly after the Civil War he started a small brewery on his Maryland farm. As demand grew, he expanded his operation. Refrigeration was the biggest problem, and that was solved by harvesting natural ice in the winter months and storing it in vaults dug into a hillside between the brewery and the farmhouse.

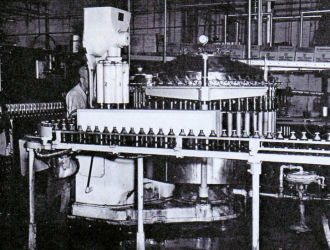

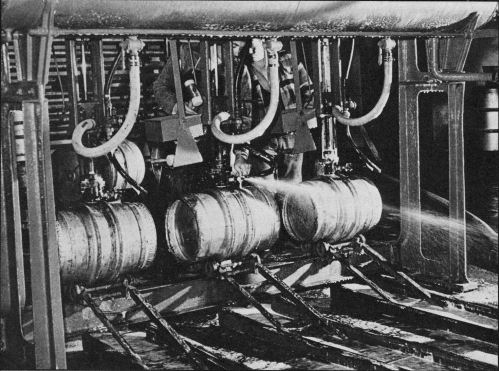

Modern machinery bottled and capped Fesenmeier beer. Date and photographer unknown. Courtesy of Goldenseal Magazine.

Eventually, Fesenmeier’s brewery outgrew his farm, and was moved into the town of Cumberland. Once things were running smoothly at the new plant, Mr. Fesenmeier returned to the farm in the country with his eldest son, George, leaving the family business in the hands of younger sons Michael, Jr., Andrew, and John. Further growth was made possible by a number of moves, both corporate and geographic.

In 1893 patriarch Michael Fesenmeier died, with his four sons and two daughters inheriting the brewery. In 1899 the Fesenmeier brothers, along with their new partner and brother-in-law, John Kearny, moved to Central City, a West Virginia community which is now part of Huntington. There they purchased the old American Brewing Company, using – according to family legend – money brother John Fesenmeier had won in the Irish Sweepstakes.

The Fesenmeiers reopened the American brewing plant as the new West Virginia Brewing Company. A major problem during the early years was the unpaved Central City roads, which became impassible to heavy brewery wagons during bad weather. The young businessmen added more horses and waited for their community to be annexed to Huntington, which offered better municipal services. Annexation came in 1909 and local street paving followed, but somehow a “Neutral Strip” – also known as Noodle Strip – between the two areas remained unpaved. For years the Fesenmeiers stationed an extra team of horses at the Strip, to help their beer wagons across the mire.

In West Virginia the Fesenmeiers settled down quickly to the business of making beer and ale, with brother John as brew master. Over the years, they’d market several brands, including West Virginia Premium, West Virginia Pilsner, and West Virginia Ale. A potent Special Export beer was brewed for sale in Ohio and other areas allowing “high test” beer exceeding the 3.2% alcohol content allowed by law in West Virginia. The Fesenmeiers were in business in Huntington for more than eight decades, and they  encountered misfortune many times during those years. In 1905 a fire gutted the brewery, and in 1913 the re-built plant was damaged by the great Ohio flood of that year.

encountered misfortune many times during those years. In 1905 a fire gutted the brewery, and in 1913 the re-built plant was damaged by the great Ohio flood of that year.

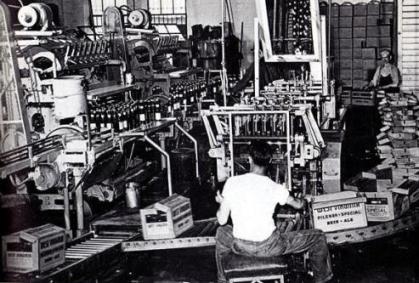

Bottled and labeled beer moved on to the packer, where 24 bottles were automatically counted into cardboard boxes. Date and photographer unknown. Courtesy of Goldenseal Magazine

Both the family and the business suffered tragedy in 1938, with the untimely death of 34-year-old Mike Fesenmeier, the firm’s secretary and sales manager. By far the biggest catastrophe to befall the company in its early years was prohibition. West Virginia went “dry” by state law in 1914, a few years before national prohibition took effect. The Fesenmeiers were left stranded with an expensive brewing facility, with no legitimate use to put it to. Like other brewers and distillers, they converted their plant to other work, first going into meat packing and later into ice and cold storage. The brewing equipment was sold at a large loss, and brewery workers who wished to continue their trade scattered to the remaining “wet” states.

Through 20 years of state and national prohibition, the Fesenmeiers never gave up their passion for making fine beer. When it became apparent in the early 1930s that the experiment with abstinence had failed and prohibition would be repealed, they began to lay plans to refurbish their old brewery buildings. By the spring of 1934, $300,000 worth of modern equipment had been installed, 30,000 wooden beer crates had been bought, and 17 train-carloads of bottles – nearly a million bottles in all – had been ordered. The country might be in the midst of the Depression, but the Fesenmeiers expected Americans to be thirsty after the long dry spell.

The modernized brewery had production capacity of 9,000 gallons daily, and the brewers had a quarter-million gallons laid by for May 5, 1934, the first day of distribution. A spirit of labor organizing was sweeping West Virginia at the time and president Michael Fesenmeier announced that union brewers would make his beer; the union label on the bottle was expected to help sell the brew to miners and other union workers.

Fesenmeier further proudly noted that “no expense has been spared in making our product the equal of any on the market today.” Even so, the bottled beer would sell at the Depression price of 10¢, down from 15¢ in 1914. The Fesenmeiers took advantage of the reopening to change the brewery’s name from the West Virginia Brewing Company to Fesenmeier Brewing Company. Of the original brothers, John and Andrew had died during prohibition, and the firm was gradually passing into the hands of the younger generation.

Brewing Company. Of the original brothers, John and Andrew had died during prohibition, and the firm was gradually passing into the hands of the younger generation.

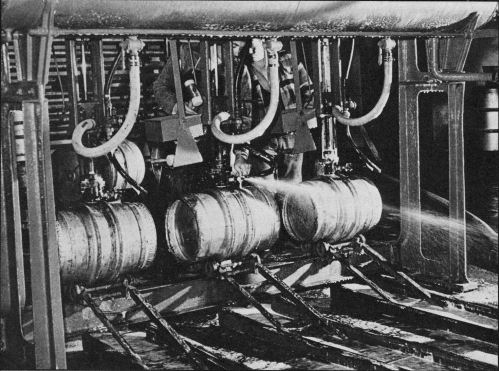

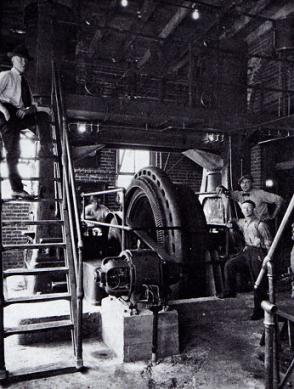

Draft beer was packed in kegs for shipment to the saloon trade. Date and photographer unknown. Courtesy of Goldenseal Magazine. (The man on the left has a mallet in his right hand. Ed.)

The aging Michael Fesenmeier retired to Maryland in 1934, turning the presidency over to J. Franklin Fesenmeier, son of John and grandson of company founder Michael Fesenmeier, Sr. The resurrected brewery would serve a large area within a 100-mile radius of Huntington. This included much of West Virginia, and parts of adjacent Ohio and Kentucky. The days of heavy beer wagons struggling through the muddy Noodle Strip were long past, and a fleet of 25 modern trucks was put on the road to serve beer distributors throughout the Fesenmeier territory. The Fesenmeier name began to appear prominently on the products of the renamed brewery, but for the first several years the company manufactured only the old kinds of beer. Toward the end of the Depression the Fesenmeiers sensed a change in local tastes and began plans for a new pilsner, to meet the demand for a lighter beer. Brew master M.A. “Gus” Fesenmeier, another grandson of the founder, was brought home from a New York brewery to supervise the change in the company’s product line.

The Fesenmeier company celebrated its 50th West Virginia anniversary in 1949 with a giant fireworks display. Fittingly, production peaked that year with a total sale of nearly 60,000 barrels of beer. After that, however, production fell by 5,000 barrels within a few years, as the family struggled with changing times. Among the problems faced by the brewery was the complex local market. Full-strength beer could be sold only in Kentucky and Ohio, with West Virginia allowing only the weaker “3.2” this meant that the Fesenmeiers had to do separate production runs of the two beverages, as did any other brewer wishing to do business in West Virginia.

The high-test sales area was severely restricted in the 1950’s, as eastern Kentucky counties went dry under local option laws. Thereafter, Kentuckians bought their beer across the river in such places as Ironton, Ohio, which was purchasing nearly 20% of the total Fesenmeier production by the mid-1950’s.The most serious postwar difficulty was the growing competition of national beer companies. Local breweries were being swallowed up by the big firms, or driven out of business altogether. This discouraging trend was as apparent in West Virginia as elsewhere, Leaving Fesenmeier as the only brewery in the state by the 1950’s. Rosemary Lyons, formerly a Fesenmeier secretary, recalled that the relative lack of advertising hurt in this battle with the nationals.

“We thought it was the best beer around,” she said. “But since it was local, people thought it wasn’t as good as the other brands. We didn’t have as much advertising as the others. We should have sold a lot more beer.” The limited advertising the company could afford was low key, using the motto “West Virginia – That’ll  Win Ya! The brewery that had weathered national prohibition might have survived the damage of local option laws to parts of its market, but it could not indefinitely withstand the pressures of competition from the national brands. Also, at this critical time the family-managed company faced another succession crisis, as the third generation passed into old age and death. Gus Fesenmeier died in 1965, to be followed by J. Franklin Fesenmeier in 1970.

Win Ya! The brewery that had weathered national prohibition might have survived the damage of local option laws to parts of its market, but it could not indefinitely withstand the pressures of competition from the national brands. Also, at this critical time the family-managed company faced another succession crisis, as the third generation passed into old age and death. Gus Fesenmeier died in 1965, to be followed by J. Franklin Fesenmeier in 1970.

Rosemary Lyons felt that the upcoming generation was less interested in taking over the business than earlier Fesenmeiers had been. Mounting pressures culminated in the sale of the Fesenmeier Brewing Company in 1968, to businessman Robert Holley of Huntington. Holley renamed the brewery the Little Switzerland Brewing Company, and added a Swiss façade to the company offices, in hopes of attracting tourists. The company kept the old brands and added a new beer, “Charge,” to its line of products.

Little Switzerland failed to become a tourist attraction, and failed in the more important business of making good beer at a profit. In a couple of years the brewery again changed hands, this time being sold at public auction for delinquent debts. The new owner, a Columbus brewer (Ohio - August Wagner - Ed.), liquidated the business, closing the doors for the last time in July 1971. A year later the Huntington Advertiser announced that the Fesenmeier buildings were being razed to make way for a new shopping center.

The sale and eventual closing of the brewery meant the loss of a way of life for the several dozen remaining workers - a life of hard but evidently satisfying work at an ancient craft, punctuated by morning and afternoon beer breaks. The Fesenmeiers lost a long family tradition of working together, and then gathering - brothers, uncles, fathers, sons, and cousins - in the firms "hospitality room" to compare notes over beer after work. Huntington lost free access to the hospitality room for civic meetings and celebrations, and lost a major city landmark to the wrecking ball. West Virginia lost its last brewery, but kept the memory of three generations of a hard-working German family. (end)

©1981 by Steve Fesenmaier

©1981 by the State of West Virginia

Brewing Company. Of the original brothers, John and Andrew had died during prohibition, and the firm was gradually passing into the hands of the younger generation.

Brewing Company. Of the original brothers, John and Andrew had died during prohibition, and the firm was gradually passing into the hands of the younger generation.  Win Ya! The brewery that had weathered national prohibition might have survived the damage of local option laws to parts of its market, but it could not indefinitely withstand the pressures of competition from the national brands. Also, at this critical time the family-managed company faced another succession crisis, as the third generation passed into old age and death. Gus Fesenmeier died in 1965, to be followed by J. Franklin Fesenmeier in 1970.

Win Ya! The brewery that had weathered national prohibition might have survived the damage of local option laws to parts of its market, but it could not indefinitely withstand the pressures of competition from the national brands. Also, at this critical time the family-managed company faced another succession crisis, as the third generation passed into old age and death. Gus Fesenmeier died in 1965, to be followed by J. Franklin Fesenmeier in 1970.