|

|

In attempting to chronicle the history of brewing beer in Charleston, West Virginia, we've found very little to go on at this point. This is what we know so far... In attempting to chronicle the history of brewing beer in Charleston, West Virginia, we've found very little to go on at this point. This is what we know so far...

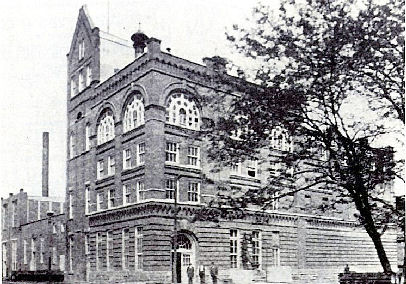

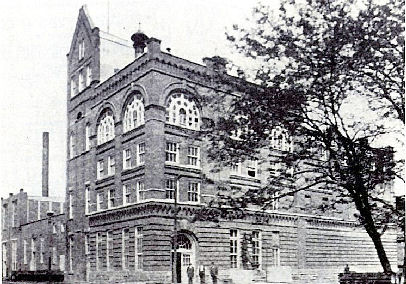

At least two brewers are said to have operated in Charleston, West Virginia between 1874 and 1878. But it wasn't until 1902 that modern full-scale brewing came to the city. The beautiful Capital City Brewing Company was built on land along Bullitt Street, south of the Elk River - about a mile from where it empties into the Kanawha River.

(right) The Kanawha Brewing Company, sometime between 1907 and 1914. Three men, most likely brewery employees, can be seen standing by the arched doorway on the right corner of the plant. (photo courtesy of Rob Musson)

Three years later in 1905, it was reorganized as the Charleston Brewing Company. But in 1906, with its most productive years still ahead, its name changed one final time. From 1907 until State Prohibition forced its closure in 1914, it was known as the Kanawha Brewing Company. During this period the facility achieved its greatest success, producing the popular Kanawha Chief Beer in bottles, which were still a new phenomenon at the time. Like many breweries, it was converted to other uses during the dry years, becoming a cold storage warehouse for a produce company.

Sadly, no more beer was made at this facility. However, beer would return to the Kanawha brewery eventually - in the form of a beer distributor that is. One that during the 1950s at least, was hawking Anheuser-Busch and August Wagner products. It is not known at this time how long they operated there. Demolition eventually claimed the brewery, but the warehouse still stands today across from Fazio's Restaurant on Bullitt Street.

It was 80 long and thirsty years before brewing made its return to Charleston. In 1994, the Cardinal Brewing Company, a micro-brewer, opened its doors to much fanfare. It was the first production beer maker in the State since the closing of the Little Switzerland company in Huntington in 1971.

CARDINAL BREWING COMPANY

Cardinal Brewing Company of Charleston, West Virginia opened in 1994 and became the first brewery in the city since 1914, when State Prohibition forced the closure of the Kanawha Brewing Company. It was also the first production facility in the state since the Little Switzerland brewery in Huntington closed its doors for good in 1971. - by J.S.

Located north of downtown Charleston on the banks of the Elk River in an industrial park at 927 Barlow Drive, Cardinal had a brewing capacity of 5,000 barrels - equal to roughly 1.6 million 12 ounce bottles annually, enough to slake the Capitol City's 80-year thirst for locally made beer. Located north of downtown Charleston on the banks of the Elk River in an industrial park at 927 Barlow Drive, Cardinal had a brewing capacity of 5,000 barrels - equal to roughly 1.6 million 12 ounce bottles annually, enough to slake the Capitol City's 80-year thirst for locally made beer.

Cardinal bottling line

Photo by Steve Exum /source unknown

The firm was owned and operated by three self-professed beer lovers: head brewer - Joe Spratt, advertising and marketing director - Mark Saber and Charleston area attorney Will Slicer. Like earlier pioneers of the craft beer revolution, all three were avid home brewers before making the decision to go professional. Spratt's dream was to make full-bodied, hand crafted beers for more discriminating drinkers who were willing to pay a premium price. What he did not want was a customer base that drank without using common sense. He felt those kinds of people should buy something cheaper.

One day he pitched the idea of starting a microbrewery to the others, who as it turns out, were already thinking along the same lines. In just a year and a half, with no prior experience operating a production brew house and nothing to guide them but their knowledge of home brewing, the trio and a handful of additional employees were cranking out New River Ale and Seneca Red Ale in bottles and kegs, and Devil Anse Lager in kegs only.

IMAGE

There was no brewpub, and by locating in an industrial park it was not feasible to add one even if needed, a decision that may have sealed their fate before a single drop of beer left the plant. Ownership saw Cardinal as a regional brewer, and made no bones about it. They did not want to tie themselves to any specific geographical area of West Virginia, so none of their brands reflected any sort of identity with Charleston or the Kanawha Valley. Labels like Seneca Red, New River, Red Fox, and Devil Anse hardly conjured up images of the brewery's true location.

Charleston's air and water quality had been the butt of jokes for a many years. Indeed, the city lies in the middle of one of the most highly industrialized parts of the United States, which includes a 25 mile stretch of the Kanawha River and its immediate tributaries. Scores of large and small chemical plants and support industries line the banks of the waterways, earning the area its famous nickname, The Chemical Valley.

Retail packaging was given special attention. An attempt was made to maximize the visual appeal by using corrugated cardboard boxes for their bottled beers instead of traditional six-pack carriers. Whether or not this had any effect on sales is unknown.

A Cardinal employee checking for quality

Photo by Steve Exum /source unknown

QUICK START

A wave of publicity seemed to give the young company the initial push it would need to be successful. Beer of the month clubs featured Cardinal brews on their rosters. Distribution spread to other parts of the State and beyond. Places like Washington, DC, Maryland, Virginia, and North Carolina were demanding their products. Plans were hatched to expand the sales territory to Cincinnati, Columbus, Pittsburgh, Philadelphia, and the Big Apple itself, New York City, the furthest possible reaches their beer could travel without undergoing pasteurization.

TROUBLE

But before they were able to capitalize on the groundswell of support, quality control rumors related to bottling and distribution began to surface. The latter may have been due to beer sitting in a distributor's warehouse undelivered until the end of its shelf life, or in some cases, afterwards. Sure, the market may have demanded Cardinal beer, but without willing distributors, the demand was more likely to go unfulfilled. What we're really talking about here is market access.

Prior to America's disastrous Prohibition experiment, most beer was consumed in saloons owned or sponsored by large brewing companies, a situation that was rife with monopolistic corruption. The current laws governing beer distribution in the United States were put in place following Prohibition as a way to prevent those monopolies of the past. This middle-man wholesaler arrangement is known as the "Three-tier system," meaning - the brewery, the distributor, and the retailer are tied together in a mutually beneficial relationship. Notice how "the consumer" is left out of this equation!

As the number of independent breweries declined between the 1930s and late 1970s, larger companies gained control of distribution channels, helping to create the very monopolies the Three-tier system is supposed to prevent. In spite of the beer revolution and the hundreds of new breweries it spawned, mega-brewers have been slow to loosen their grip on the distribution system, making it hard for smaller companies to access the marketplace.

For instance, Anheuser-Busch controls roughly 50% of the US beer market and 70% of their distributors carry only A-B products. Any distributor whose existence depends on a single mega-brewing company like A-B is not likely to rock the boat by carrying a competing brand and risk having A-B pull their account, effectively putting them out of business. Since the vast majority of US beer distributors are sponsored by one of these brewing behemoths, guess who decides which beers go on the delivery trucks?

BREWPUB BREWPUB

Less than a year into full operation it had become apparent that Cardinal was going to need a brewpub to boost retail sales in their home market. Adequately showcasing their beers on a consistent level was next to impossible.

Cardinal products

Photo by Adam Patnoe

A brewpub has no distribution issues. Its products are generally consumed either on-site or taken home in half-gallon jugs (growlers). Distribution normally consists of kegs being sent to local taverns and in some cases, allowing select beverage stores to carry growlers. Brewpubs have the freedom to experiment at-will, often producing a wider range of styles, with the additional luxury of a built-in tasting panel in its bar patrons, who tell them directly if the beer is good or not. Back in the 1990s, as it is now, distributors and especially retailers as a whole lacked even a basic concern for craft beer.

By going straight to bottling in an industrial park where zoning laws wouldn't permit a brewpub without red tape and where few people would desire to visit one anyway, and by stretching distribution beyond the local market, Cardinal found itself in a fight with the neighborhood bully, Big Beer. Consumers and retailers had long ago been duped into believing that all beer is light-yellow fizzy stuff. Nowhere was that more true than in West Virginia.

In June 1995, Cardinal ownership partnered with a new group called Capitol City Brewing Inc. to open a brewpub in downtown Charleston in the former Catfish Willie's restaurant at 28 Capitol Street, a project which never saw the light of day. According to several accounts, an order was placed for the brewing equipment before the project fell through. It is worth mentioning that a few other well-publicized ventures for brewpubs were planned for Charleston by separate individuals during this period. None came to fruition.

BIG CHANGES

In the summer of 1996, Cardinal ownership expressed a desire to produce pasteurized beers that could travel great distances and have a longer shelf life. Having re-evaluated the company's goals and citing their inability to pasteurize, coupled with the high cost of bottling in Charleston, production was shifted to Stroh Brewing Company's Winston-Salem, North Carolina plant on a contract basis with Joe Spratt supervising.

In another move, the New River and Seneca Red brands were dropped and Devil Anse became the company’s flagship. Cardinal had planned to roll out a whole line of new products, but only a lager and a porter were ever produced. Kegging operations continued in Charleston for a time but it is not known for how long. Their brewing equipment was sold to the North End Tavern (The NET) in Parkersburg, West Virginia, a small neighborhood gathering place on the city's north side that opened in 1899.

Owned by Joe Roedersheimer since the late 1970s, the NET simply added a brewpub to their century-old tavern and called it a day. A partnership was to be formed between The Net and Cardinal Brewing but this was short-lived if it happened at all. The Net remains in business today, and continues to produce high quality beer.

THE END

Meanwhile, the brewing-behemoth Stroh, once a major regional, was straining under the weight of going national through a series of ill-advised acquisitions beginning with Schlitz in 1982 and ending with G. Heileman in 1996, turning the once lean and mean machine into a sweaty, bloated, ailing giant. Saddled with excess brewing capacity, Stroh and companies like it were desperate to find small breweries like Cardinal to fill the void. For Stroh it was not enough, three years later, they were out of business, their brands absorbed by Pabst.

By the fall of 1996, the idea of a downtown brewpub was floating around again in the Cardinal office, with an opening date projected for some time in 1997. Sales of the Devil Anse line were strong with distribution in five states, selling more in two months than the New River brand sold in an entire year. However, Stroh soon went into bankruptcy, which had a direct impact on Cardinal, eventually leaving them with no place to contract brew their products.

Given the right circumstances, this brewery might still be here today. In spite of Cardinal's misfortunes, their beer was good, and they should be hailed as pioneers of the West Virginia craft beer movement.

CARDINAL BREWING COMPANY - Labels & Brands

Sorry, these pictures do not enlarge and we're not even sure where we got them. If you have larger examples, please let us know!

|

|

|

|

In attempting to chronicle the history of brewing beer in Charleston, West Virginia, we've found very little to go on at this point. This is what we know so far...

In attempting to chronicle the history of brewing beer in Charleston, West Virginia, we've found very little to go on at this point. This is what we know so far...

Located north of downtown Charleston on the banks of the Elk River in an industrial park at 927 Barlow Drive, Cardinal had a brewing capacity of 5,000 barrels - equal to roughly 1.6 million 12 ounce bottles annually, enough to slake the Capitol City's 80-year thirst for locally made beer.

Located north of downtown Charleston on the banks of the Elk River in an industrial park at 927 Barlow Drive, Cardinal had a brewing capacity of 5,000 barrels - equal to roughly 1.6 million 12 ounce bottles annually, enough to slake the Capitol City's 80-year thirst for locally made beer.

BREWPUB

BREWPUB