|

MY DAD'S BREWERY ARTICLE

Fesenmeier's Mark Golden Anniversary

By ERNIE SALVATORE What follows is the first big feature story written by my late father when he was a cub-reporter for the Herald-Dispatch. My parents were newlyweds at the time of its publishing. Later he would become a famous sports writer. I find it ironic that it was only after I built this website that Dad told me about his Fesenmeier article. Fans of his writing style will recognize early signs of what were to become some of his trademarks. Learn more about Dad by clicking here: Ernie Salvatore. - J.S From the combined Sunday edition of the Herald-Dispatch and Huntington Advertiser. The Herald-Advertiser - Sunday May 22, 1949

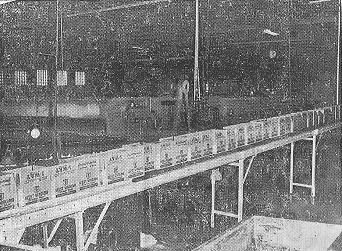

Fifty years doing anything is a mighty long time but to the incumbents of the Fesenmeier Brewing Co. of Huntington, the celebrating of their 50th anniversary of business this year will mark just another short milestone in an already gratifying career. In fact, as Frank Fesenmeier, president of the company said during an interview this week, “this is only the beginning. The first 50 years were the hardest. Now we’re ready to begin.”  CLEANLINESS PLAYS a big part in the brewing of beer. Shown here (right) is a long line of orderly bottles, recently filled with beer, about to enter a pasteurizing machine. The long rows of half-cases running along the right side of the picture have been filled with bottles after they pass through the pasteurizer.

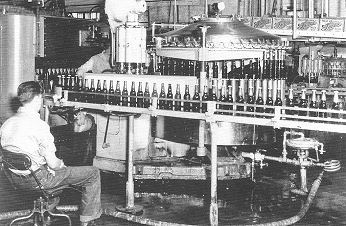

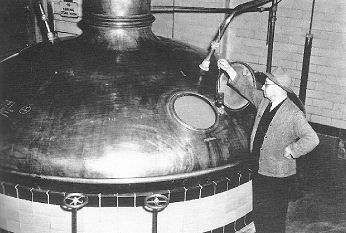

Quaffing a few ten-ounce glasses of lager in the Fesenmeier tap room, which is an exquisite place with all the atmosphere of a genuine German beer garden, Frank and his brother Gus, the present brewmaster; and tall, lean, affable George J. Linsenmeyer, the sales and advertising manager for the firm – discussed with the writer various possible ways of producing this story. Mr. Linsenmeyer suggested a recapitulation of the brewery’s long and respectable history here in Huntington. Frank and Gus nodded in assent. However, newspapermen being hard-headed, this was rejected by the writer in favor of another approach. “LET’S GIVE them the story of the bottle or glass of beer” the writer suggested. “Let’s give them the whole romance of producing your product. People are afraid of history because there are too many dates.” This idea was adopted unanimously. So a few lagers later, in the company of George Linsenmeyer, this is the story that unfolded before the eyes of a lay beer lover: Beer is truly a beverage of moderation, manufactured with all the care, integrity, and patience of great artists. WITH COUNTLESS numbers of federal regulations to observe and with the ever present shadow of a return to prohibition confronting them – the makers of beer are truly people of stouthearted ken. But they wouldn’t have it any other way. “It makes us work harder and longer to present a temperate beverage that the working man can consume in moments of relaxation, “George said. “It makes us work harder to prove that we are in a respectable and fine business – free from the stains of the many charges that are always being thrown at us.” BUT GEORGE didn’t spend too much time philosophizing. Instead, in capsule form, he completed a swift tour of his brewery explaining the story of a glass or bottle of beer.  EVERY BOTTLE of beer that Fesenmeier's place on sale is checked for purity and a lack of foreign substances. Shown here (left) is a line of beer bottles which have just passed through the pasteurizer and have been crowned with caps in the circular device seen in the center. They then pass before the inspector, shown at the left, who with the aid of a powerful light placed on the far side of the bottles, can detect any impurity that may have crept into a bottle. The first stop on this trip is the mash tub [tun] into which grain and water are placed. The grains and water are agitated to get starch and sugar. In all, this tub holds 300 barrels of water and 12,000 pounds of grain – which is in the heavyweight class. Incidentally, the grains are malt and corn flakes. When this step is completed, the grains are strained off to form a liquid known as wort, i.e., the name of the liquid when straining is completed. This takes place in a lauter tank where the remaining grains are pushed into a hopper and sold to farmers as cattle feed. During the process of straining in the lauter tank, the grains gain 30 percent of proteins. The wort is then drained off in tubs. The brewmaster, Gus Fesenmeier, checks the liquid for clearness and if it isn’t clear, he pumps it back into the lauter tank. If the liquid is found to be clear, he pumps it into a brew kettle. Made entirely of copper and resembling a giant tea kettle, the brew kettle is one of the most picturesque pieces of equipment in the plant. In it, hops are added to the wort or strained liquid. Eight u-shaped pipes fastened to its sides force steam into the kettle in order to boil the wort. This boiling is done to get the true essence of the hops into the liquid. In the center of the kettle floor is a hop-strainer which handles the runoff from the hops after the kettle’s chore has been finished. AT THIS POINT the wort drops into the hot wort tank from the beer kettle. Any sediment in the liquid will drop to the bottom of the tank while the wort itself is pumped into a “cooler room.” In the “cooler room,” which is its name and not a description of it, the beer (we can call it that now) is pumped through to the top from which it trickles down over copper and cast iron pipes. Ammonia is pumped through the copper pipes and brine through the iron pipes, while the beer is trickling down. This enables it to be cooled from 180 degrees to a chilly 40 degrees. From the “cooler room” the beer is pumped into settling vats where yeast is added. The beer remains here for a day which allows an activation of the starch and sugar, causing fermentation. These vats, there are three of them, are glass lined. At this point, George pointed out that the brewing process of one batch of beer would have reached 14 hours. From the settling vats, the beer is pumped into the fermenting room where it does just that (fermenting) for 10 days in order to attain the legal desired alcohol content. While the fermenting is in progress, carbon dioxide is drawn off and stored. It is later added to the beer for carbonation purposes. All of the fermenting tanks are glass lined and after they are emptied, they are subjected to a thorough scrubbing and an inspection for chipping.  NO, THAT isn't a hot water kettle pictured here (right). It's a copper beer kettle which plays a very important role in the brewing of West Virginia beer at the Fesenmeier Brewery. The late Joseph Wertin, who was the assistant brewmaster at the brewery before his death, is shown examining the liquid. In this operation, hops are added to the wort (the beer is called "wort" in the early stages after the grains are strained off). The wort is boiled in this kettle to get the flavor and essence of the hops.

Next the batch of beer is pumped into a stock room or cellar where a temperature of 34 degrees is maintained. Here the beer is pumped into more glass lined tanks for an aging period which varies between 50 and 60 days. It has a capacity of 15,000 barrels which, by the way is 4,950,000 bottles of beer. (A lot, huh?) FROM THE STOCK room the beer is sent to one of two places. If it is to be used in draught taps it is pumped into a racking room or if it is to be bottled it goes to a bottling house at one end of the brewery’s grounds. Just outside the stock room is a government meter which keeps check on every drop of beer that goes into the racking or bottling rooms. In the racking room the beer is filtered and then pumped into a racking machine, where through tubes, it enters a keg, while air is drawn off from the keg at the same time. There is a special keg washing room where all kegs are washed in an alkaline solution before going into the racking room to take on a load of beer. EACH WASHED keg is lined with pitch, also. In the bottling room, returned bottles are fed into a bottle washer where they pass through five solutions of alkali and are brushed inside and out four times. To top this off, each bottle is rinsed four times inside and out. “And, everything we use to clean the bottles with,” George said, “is thoroughly scrubbed and cleansed too.” “Just like the Army,” was the writer’s comment, with tongue in cheek. After being washed and scrubbed and rinsed, the bottles are fed into a filler and from the filler to a crowning machine. After passing the crowning machine the bottles go through a pasteurizer and then are labeled, with each label dated in code. From the labeler the bottles are fed into cases – and from the cases they go onto the trucks – from the trucks to the stores – from the stores to your kitchen ice box. That’s the story of beer. Anyone who thinks creating a batch of grog is amateur stuff had better re-read the process. For, in all of these stages there are trained men working under Gus Fesenmeier – men who know how to ply their trade. Fesenmeier’s brewery is one of 400 left in this country – where formerly there were 2,000, with the 1,600 delinquent breweries becoming so because of the expansion of the larger ones. It is the only brewery in West Virginia. It has a reputation in the art of brewing as one of the best in the country – ranking high in the first third. It produces between 80,000 and 90,000 barrels of beer a year or between 29,700,000 to 30,000,000 bottles a year. FRANK FESENMEIER added a final, natural touch to the story when he said, “People are constantly calling us up and demanding that we go out and clean up the beer gardens. We’d like nothing better – but we don’t have the power to do so." |